ABOUT SCOTT FRANKLAND

Scott Frankland is Head of Content at Sengerio. His spirit of inquiry leads him to the world of transportation and mobility to connect with the industry’s leading experts and shine a light on the hot topics.

Transport and mobility…

Is there a difference here and, if so, what is it?

From a linguistic perspective, it’s an interesting question and it reflects the nature of how our language is continuously evolving (take it from a Brit who’s writing for a North-American audience!).

With a bit of thought, the majority of us might even struggle to break a clear division between them.

But if we take a look into the semantic microscope, the blurry line between the two terms begins to sharpen.

You don’t need me to tell you that transport describes the movement of things, people, animals, whatever comes to your imagination– it’s the standard A to B model– and does exactly what it says on the tin.

However, transport and its A to B model often overlook or trivialize how people move:

This is where mobility comes in.

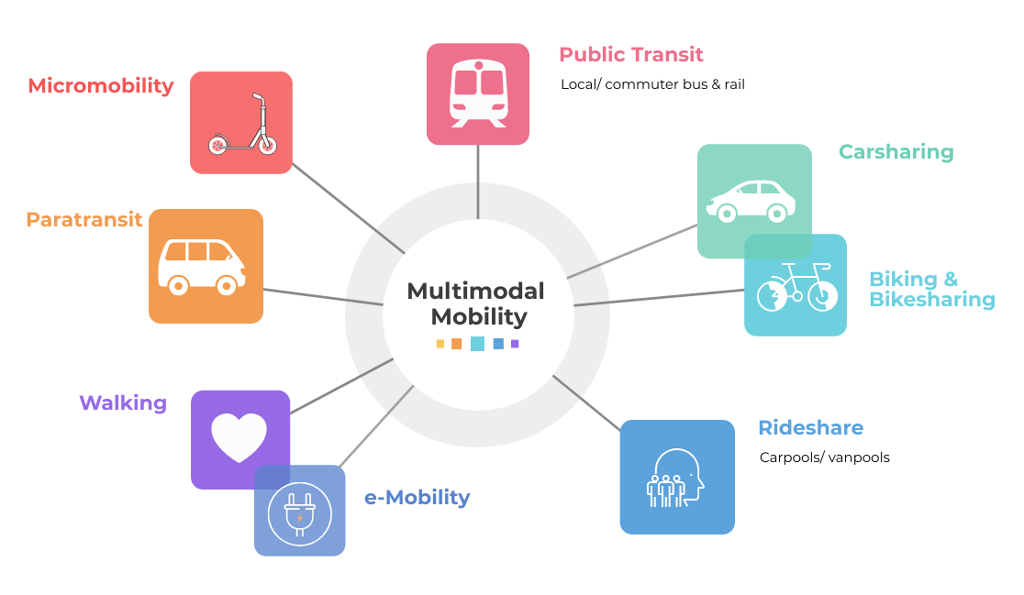

Mobility is the ability to move freely and sustainably by providing a variety of transport modes, from public and private transit to walking and biking and much more.

It isn’t just about having access to transport. In fact, if mobility fails, so too does transport.

This makes mobility a critical element to every transportation project from urban planning that’s striving for the ‘15-minute city’ concept to rural networks by ensuring that every person within a community can get around efficiently and sustainably.

But enough of my semantic digression!

A warm welcome to the first chapter in Sengerio’s miniseries on everything mobility, where we connect with the mobility world and its leaders to delve inside and have a look around at how transportation is evolving.

Now we’ve established what mobility is, let’s see what it does…

Since the mid-twentieth century, single-occupancy vehicles have been the dominant mode of transportation and have had a significant influence on the developmental history of our cities.

But as our civilization progressed and the population increased, this created more problems for our built environment to accommodate more people using private vehicles.

Traffic congestion. Full parking facilities. Mobility solutions for non-drivers. These are some of the common examples of transportation problems.

So how do we go about resolving them?

Our usual go-to solution has been to create more of these resources; more roads and more parking— problem solved, right?

Wrong. This approach only adds fuel to the fire. That is, it creates a vicious circle where the solution only feeds back to the initial problem.

By increasing the roadway capacity we only induce more private vehicles onto our roads which consequently puts us back to where we started— congested streets with no parking.

And for the non-drivers? While it’s true that public transit, micro-transit, and paratransit greatly reduce the total number of single-occupancy vehicles on the road, these solutions still find themselves gridlocked in the same traffic as everyone else.

In 2021, our excessive dependency on private vehicles is taking its toll on our environment, health quality, and even our lifestyle.

This narrow, mechanical approach of observing our transportation problems and aiming to resolve them simply by creating more of it is inefficient, unsustainable and completely overlooks the bigger picture of mobility problems.

To understand how we can resolve these problems, we have to look closer at their roots and understand that the solution lays at the fundamental level of each individual who wants to connect with the community.

We need an approach that emphasizes the movement of people, rather than just motor vehicles. An approach that considers how individuals behave and rationalize their mobility choices to establish a diverse transportation system that’s efficient and accessible to all members within that community.

Welcome to the world of mobility management.

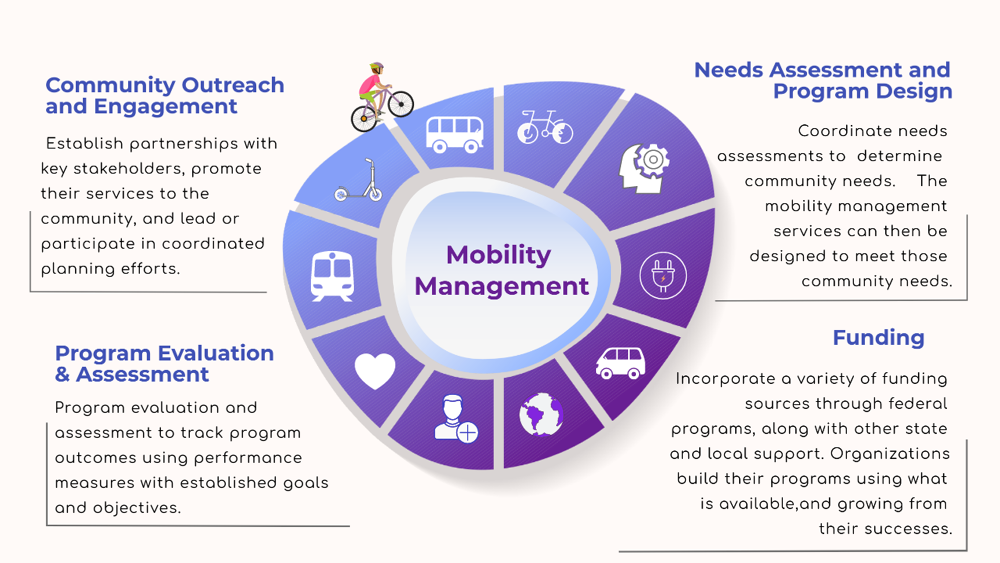

Mobility management, also commonly referred to as transport demand management (TDM), assimilates a wide range of transportation modes and service providers to increase transportation systems’ efficiency and promote sustainable transport solutions.

According to the definition of the Association for Commuter Transportation (ACT), a premier organization for mobility and TDM specialists, TDM strategies aim to create efficient, multimodal transportation systems that move people with the goal of reducing congestion, improving air quality, and stimulating economic activity.

The approach achieves this by utilizing strategies, policies, and existing infrastructure to reduce the demand for single-occupancy vehicles by influencing people’s attitudes and behavior choices when it comes to choosing how to travel.

With the scope of reducing our dependence on private vehicle ownership, mobility management unleashes an abundance of different strategies that each have their own huge array of benefits, such as:

• Commuter Benefits and Transport Equity

To influence travelers’ habits and transport choices, mobility management deploys both positive & negative incentive strategies that make alternative mobility modes more enticing than driving.

Some examples of these positive incentives are initiatives that support increased levels of walking and biking, which enhance the quality of life and promote healthy living. Financial incentives may also be provided to render other modes of transport cheaper than owning a private vehicle.

Negative incentive strategies ramp up the direct costs associated with driving, such as congestion fees and parking fees. But negative incentives can be perceived as contradictory to the fundamental principle of mobility management and have previously been a point of criticism since it makes mobility less affordable to some users.

In general, mobility management increases the overall accessibility of transport by ensuring transport prices reflect their actual costs. As a result, this benefits a greater proportion of a community by improving affordable mobility choices.

• Sustainable Mobility

Mobility management’s philosophy underpins the sustainability of transport by integrating sustainable principles into its strategies.

In fact, mobility management and sustainable transport share a certain synergism in their objectives by promoting equity, a cleaner environment, and efficient land use.

• Flexible Solutions

Depending on the level of implementation and scale of a given program, mobility management targets specific groups within a community that can be categorized according to a specific demographic.

This could also be a socioeconomic characteristic or a particular reason why a given community wants to travel.

The flexibility that mobility management provides in targeting specific groups has made it a powerful tool for improving site, urban, and even regional level mobility. It has both the incredible ability to tailor a program for a neighborhood while the parallel neighborhood may require a completely different approach.

To get a better understanding of how mobility management is applied in the real world, Sengerio delved into university transportation that packs its own set of mobility challenges.

As today’s leading universities continue to expand, they require more intricate mobility planning to ensure that students and staff can easily access campus and buildings without having to build more traffic infrastructure.

— by now we’ve learned that only building more traffic infrastructure such as roads and parking facilities only exacerbates additional problems!

There are many factors to consider before implementing a mobility program at an educational institute such as a university.

For instance, an initial observation would be the design of the university’s campus (or campuses), how it is situated geographically, and considering the existing infrastructure and how they can be incorporated into a mobility strategy.

University campuses are generally well structured to accommodate a variety of mobility modes, especially pedestrian and cycling modes. The total number of students and staff living on or near campus also facilitates mobility management strategies as the total amount of land that needs accessing is greatly reduced.

Stanford University represents a prime example of this, where 93% of their undergraduate students live on-campus and 59% of its commuters used alternative, non-single occupancy modes of transport in 2019.

This is thanks to the large investment in safe and efficient on-campus and peripheral infrastructure accompanied by the necessary services and facilities to accommodate its commuters’ mobility choices and behavior.

Not to mention, of course, the additional incentives Stanford University offers its member community to adopt these alternative modes of mobility.

On the other hand, UC Berkeley has fewer students than live on-campus. For this reason, greater attention must be turned to off-campus solutions to coordinate an efficient mobility program within an existing network to and from the university.

Both Stanford and UC Berkeley provide their own shuttle service for on-campus transportation and a first-last mile solution to connect the university with other major transport stations such as Caltrain and BART, respectively.

The universities also utilize the existing public transit lines of VTA and AC Transit, respectively, and provide free and/or highly subsidized passes to their member community along with real-time transport information to keep riders updated.

Mobility specialists continuously scrutinize the price of these transit passes in order to ensure it reflects an accurate cost of the transport expenditure. The point here is that commuters remain better-off using transit solutions rather than investing in a private-vehicle.

University transportation has many more depths of mobility complexities that constitute a successful program— of which this article merely scrapes the surface.

However, the key takeaway is that mobility strategies really do encompass the bigger picture and address every single component that may affect a traveler’s commuting habits. Keeping in mind that these components undergo a perpetual fluctuation that mobility specialists need to balance to ensure the long-term objectives are still met.

We’ve seen perfectly well how the pandemic has enabled us to adopt teleworking. But with the vaccine program beginning to roll out, mobility leaders are anticipating the return of commuters as early as this fall.

From the perspective of a mobility specialist, the crisis has reshaped how we think about transportation choices and consequently, our behavior has been influenced.

With safety on top of everybody’s list of priorities whenever they leave their house, many people dislike the idea of getting on a crowded bus and using other shared mobility. As a result, more people are likely to choose to travel in a privately owned vehicle.

This behavioral change elicits a series of new problems that mobility specialists must challenge to succeed in a post-pandemic world. I asked a Transportation Demand Management Specialist at UC Berkeley about the future challenges for mobility in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Since the initial shelter last March, we are already seeing an increase in traffic volume. This means that people need to make the big decision as to whether they want to tolerate the traffic every day or understand and be convinced that public transit is going to be safe.

Not only that, but given that public transit agencies aren’t running 100% of their services, we are anticipating an onslaught of parking demand.

The question from our end is how are we going to convince people that using public transit is safe and that all the protocols have been met.

A lot is on the line as to whether our communities will reopen completely or if a hybrid model will remain implemented to more effectively manage the total volume of people traveling during peak hours.

If the latter occurs, the question arises as to how mobility specialists can integrate hybrid models into transport strategies and alleviate a high parking demand.

In any case, to eliminate a sharp rise in privately-owned vehicles, we need to resuscitate public transit networks so that this new and evolving ridership demand can be met.

Let’s take a closer look at the shape of Bay Area’s public transit.

Within the 9 counties of the San Francisco Bay Area, a total of 27 public transit agencies operate each within their own territories.

Due to this vast quantity of agencies, public transit in the Bay Area has received some criticism over the years because of the lack of coordination between them that has resulted in a fragmented transportation network.

As a way to overcome these difficulties, back in May 2020 the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), the main planning, coordinating, and financing agency in the Bay Area, put together a 32-member Blue Ribbon Transit Recovery Task Force to support the future of Bay Area’s public transport network, that has been shaken by the pandemic.

The MTC and the BRTR Task Force are working on the critical network across the region and are striving to establish more partnerships across the 27 transit agencies. By doing this the agencies can provide more services where they are needed most, ensuring that enough vehicles can satisfy the most popular routes.

We have already seen 9 of the 27 transit agencies converge in a Twitter thread in order to coordinate their service information— together!

For me to attain a better understanding of these partnerships, I had the pleasure of chatting with Jessica Alba, Transportation Policy Expert and Chair of the Board of Trustees at the Association for Commuter Transportation, about the current situation between the Bay Area transit agencies and how they are preparing themselves for the post-pandemic world.

Jessica shared her expertise on the subject and expressed her optimism for the future of public transport in the Bay Area. In addition, Jessica highlighted that the pandemic has actually created an opportunity for the agencies to improve how they communicate with one another. As she explains,

Now that everyone is using Zoom, you can bring the 27 transit agencies into the same space and get everyone on the same page with a simple 10 minute presentation, that’s facilitated by someone who really understands the importance of a seamless transportation network.

This has been a huge boost with regards to the coordination between agencies, which is something we desperately need right now. In the past, the lack of coordination has been evident to public transit users especially when they transfer from one transit agency to another.

Currently, the Bay Area public transit agencies provide services at an approximate rate of 50-80% of their pre-pandemic levels, which in general is still fairly good coverage— naturally, they do not have their usual pre-covid frequency.

But for mobility specialists, the challenge is determining whether the public services can support the sudden rise in people wanting to use transit again once our communities reopen.

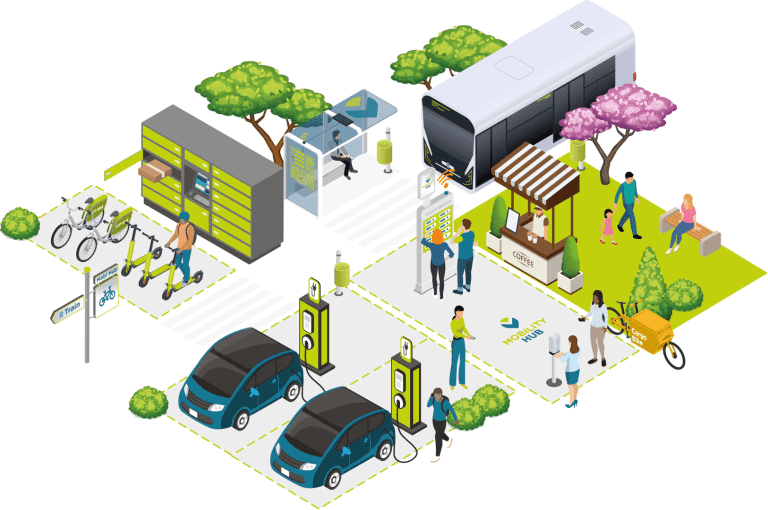

Transport agencies have realized they need to be more nimble. So many agencies are implementing pilot programs and are partnering with ridesourcing companies like Uber and Lyft as well as other microtransit providers.

A recent article published in the National Academies Press brings to light the growing number of agencies integrating microtransit services in the Bay Area.

Not only does this allow private microtransit companies to fill in the gaps where the fixed lines of public networks don’t reach, but it renders transportation more equitable to smaller communities that do not always have access to the bigger, more established networks.

As the Bay Area marches towards a more unified, seamless transit network, the next challenge will be to ensure commuters that these services are safe and reliable.

In addition to the MTC and fellow transit agencies ramping up community outreach and engagement to promote their services, it will be interesting to see how they address people’s specific needs in a post-pandemic world to make public transit seem a more viable solution than driving.

The world of mobility is quickly evolving and new challenges are arising each day.

Mobility management provides the gravity of the transport world by holding everything in its place and ensures that it continues to function in a coordinated and seamless manner.

Getting even closer, today’s mobility specialists are the artists staring at the blank canvas, armed with a plethora of tools to create the next masterpiece.

A masterpiece that consists of mobility networks bringing communities closer together in a cleaner, more equitable, and more sustainable environment.

And as they begin to sketch what our transport networks will look like in a post-pandemic society, we are slowly beginning to notice the nuances of a network where mobility solutions are more connected than ever before.

While this first chapter in Sengerio’s miniseries on mobility management has merely scratched the surface of its complexities, it has served as an overview of what mobility management is, its importance, and how it can be applied in a variety of contexts.

Be sure not to miss our next chapter where we’ll dive into a more specific area of mobility management and learn from the experts who are utilizing it for the future of transportation!

ABOUT SCOTT FRANKLAND

Scott Frankland is Head of Content at Sengerio. His spirit of inquiry leads him to the world of transportation and mobility to connect with the industry’s leading experts and shine a light on the hot topics.