ABOUT SCOTT FRANKLAND

Scott Frankland is Head of Content at Sengerio. His spirit of inquiry leads him to the world of transportation and mobility to connect with the industry’s leading experts and shine a light on the hot topics.

Over the past few years, we have witnessed a huge change in the way services and products are provided.

We have seen consumers drift away from their firm stance towards ownership and gradually adopt a rapidly evolving ‘shared’ economic model. As a result of this, several business giants have emerged thanks to their ability to capitalize on the so-called ‘as-a-service’ models.

The extent of this shared economy spans way beyond transportation– take Airbnb for instance – but if we come back closer to home to the world of mobility, it’s evidently cruising in the same direction.

With today’s urbanization, population growth, and environmental challenges, the current vehicle-centric system is being disrupted by a more efficient, personalized system, in what has become well-known as Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS).

What exactly is MaaS?

In their white paper, the MaaS Alliance defines MaaS as:

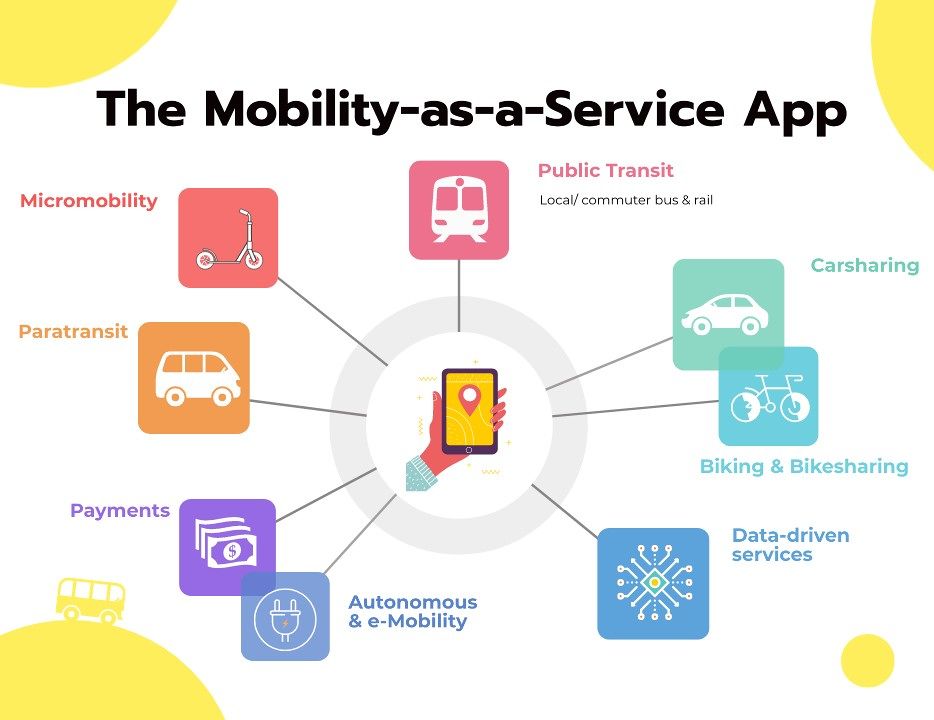

This means that for users, MaaS reshapes how they access mobility by allowing them to plan, book, and pay for their transportation services directly from their smartphones, this includes public & private transit, micro-mobility (i.e. Bike- and scooter-sharing), taxis, car sharing, car rental and rather importantly, a combination of the modalities.

In its essence, MaaS creates a network of (mobility) networks by providing the interstitial connectivity needed to support a variety of mobility modes so that they are viable, easy-to-use, and frictionless.

On top of that, MaaS can even be implemented as a mobility management tool to introduce more travelers to shared mobility. But we will get stuck into this later—

First off, we need to understand the bigger picture of transport and mobility today and look at the transition it has been going through within the past twelve months. Only then are we able to see why MaaS has a huge role in its development.

To better comprehend MaaS’s place in the mobility toolbox, we have to switch lenses and look at the transportation industry from another perspective. A perspective that recognizes the transition from the existing transport model which is based on private car ownership to a shared model of mobility.

To learn more about this, Sengerio had the pleasure of talking with Timothy Papandreou, Founder of Emerging Transport Advisors, who provides guidance to businesses, institutions, governments, and investors, on how to best prepare for the coming innovations with regards to shared, electric, and automated transportation trends.

Timothy explained how the technological progress being made in supporting the way in which we create our cities and transportation networks is moving us closer to a system where everything is connected to everything.

What’s underlying these three forces converging is the digitization and the digital transformation of everything connected to everything and all those connections making it possible for these three forces to accelerate.

Within the next decade, we’re going to see more and more pilots and deployments. Eventually, the transition is going to snowball and the new system will start to establish itself and the network effects will start to show.

Not only is the transition streamlining the converging forces, but this interconnectivity is strengthening the dynamics of the system so that it can withstand potential ‘shocks’.

Meaning that when one area of a network undergoes some form of change that causes it to operate suboptimally, another area of the same network can compensate by providing additional resources to accommodate the shift.

This interconnectivity is especially paramount in today’s mobility strategies where we are going to need to welcome a more flexible model of how people want to move around, as Timothy highlights:

With the pandemic, we have had to accelerate these things and people have had to get on board with the digital transformation. We’ve seen that what was supposed to happen in the next two years has had to happen in as a little as two weeks.

For example, we’ve seen transit agencies forced to redesign transit systems in a matter of days. We’ve also seen cities put in temporary bike lanes and social distancing spaces, as well as working closely with small businesses to allow them to use the public roadway that was previously dominated by private vehicles.

This isn’t going to go away after the pandemic, much of this is becoming permanent. I think that we have come to understand that it has worked and that we need to keep moving in this direction.

This raises the question as to how we can imagine the future of mobility and its relative management strategies.

With more modalities and supporting infrastructure at our disposal, how will this change our approach to transport demand management to ultimately achieve our mobility objectives?

If we want to provide safe, reliable, sustainable, and affordable mobility that’s accessible to all members of a community, we need to look at today’s standard A to B model and realize its solutions lack consistency and efficiency.

Instead, we must concentrate our attention on providing mobility solutions at the lowest price, using the lowest amount of space, and utilizing the smallest means of transport possible, as a way to guide travelers’ choices when planning their next journey.

Only by getting these three parameters to work synergistically will we notice people eventually become more flexible in their mobility choices in accordance with the demand of a particular mode.

With MaaS’s ability to increase the uptake of shared mobility modes, its concept has taken the transportation industry by storm as it gives rise to several positive impacts for travelers and transport providers.

MaaS encourages the shift from individuals relying on personal vehicles to promoting the adoption of shared mobility to significantly reduce traffic congestion and parking demand.

This avoids the need to invest in more costly ‘vehicle-orientated’ infrastructure that only adds to the burden. Not forgetting, of course, that reducing the volume of vehicles on the road ultimately makes roads safer, more accessible, and produces less greenhouse gas emissions.

In addition, it transforms a land of competitors into a network of partners by essentially allowing public and private providers to work side-by-side.

Therefore, cities and organizations that adopt MaaS work closely with private providers and ensure that operations are frequently utilized and reduce unnecessary services.

This helps define transportation markets for private companies and provides a way for the regulatory bodies to ensure the available services abide by the set standards.

Generally speaking, this creates an open playing field for many types of mobility providers to seamlessly deliver shared mobility solutions, as well as paving the way for the emerging mobility services such as self-driving autonomous vehicles (AVs) to be integrated into the MaaS ecosystem.

Now that we have looked at how the rapidly evolving transportation system is thriving off the digital transformation to provide better mobility to the community, and how MaaS brings together all of its advantages to provide a personalized on-demand experience for its users, we can take a better look at the structure of a successful MaaS system.

More often than not, the introduction of new MaaS applications grabs the headlines as the solution to mobility’s problems. But the application is only the resulting connector of a successful system that has well-established foundations.

So what’s needed for a MaaS program to work? Let’s take a look at the four pillars of a successful MaaS system.

As with any mobility project, the potential users are central to its success. For this reason, it’s essential that the stakeholders are aware of the gaps in their transport system which a MaaS system could resolve.

Our objectives must be to distribute mobility solutions to the widest possible audience and given that MaaS’s future is yet to be fully understood, a lot is on the line as to whether people will truly want to switch from their personal vehicles and opt for a shared mobility model.

If we simply choose to bombard our communities with a high-tech alternative to driving, we run the risk of excluding the poorer, more limited communities in favor of the ‘tech-savvy’ population.

To achieve a successful MaaS system, cities must tailor their mobility strategies to the context of their potential users to fully comprehend whether they would benefit from MaaS’s advantages.

This includes understanding how MaaS could provide equitable transportation; reduce congestion, parking demand, and pollution; promote an active lifestyle and incentivize existing public transport networks.

Every modality is only as efficient as its relevant infrastructure allows it to be.

During Sengerio’s conversation with Timothy, he pointed out that today there generally isn’t a shortage of providers. Instead, we lack the necessary infrastructure to support these providers which consequently affects travelers’ behavior when it comes to selecting an alternative mode.

Shared Mobility providers often struggle to be profitable because the infrastructure just isn’t there to protect them. For example, with bike-share and scooters, they tend to find it harder to establish themselves in places that lack dedicated lanes and pick up and drop off spots for them to operate so that riders feel safe and comfortable using the system.

We often focus our attention on asking why travelers are hesitant in adopting new mobility solutions that we completely overlook the important role cities have in investing in the infrastructure to accommodate these changes.

It is often the case where it is the governing body that is more tentative in making the switch due to the high costs of investing in new infrastructure— this goes back to our reluctance of letting go of the car-centric transport model.

With governments spending 50-70% of their infrastructure budget on simply maintaining or replacing the existing system, a lot of resources are currently being poured down the drain that could be redirected into the MaaS ecosystem.

If you have a city that’s designed for cars, we shouldn’t be surprised if more people are driving and not using other mobility modes. Cities subsidize public transport for all the right reasons, but they subsidize private car travel to the point that it skews the viability of these shared options. We need to look at how public agencies can support these shared mobility options with public transport to create a more level playing field for mobility and access in our cities.

A successful MaaS program is built upon the existing public transportation network which is then reinforced by private providers to fill in the gaps. Together, this cooperation between public and private providers can satisfy travelers’ needs through a multitude of transport modes.

A key component to MaaS’s interconnectivity is the ability to analyze and share mobility data between organizations in order to provide better solutions. This is beneficial to all parties of the MaaS ecosystem, including travelers, as they have access to more options with greater trip efficiency. Timothy explained that:

We have to look at cost-effective ways to see the big picture. Data companies can really help out by understanding the full cost of the system. From this, we can really see the benefits. If people really want to make a climate dent in their cities, they need to fund more frequent, more reliable public transport and shared mobility services.

At the moment, travelers don’t have access to all the information about their mobility options (without having to utilize several different resources). MaaS’s capacity, along with transport providers’ willingness, to share mobility data facilitate many elements of a successful MaaS system.

This includes multimodal trip planning and real-time mode connectivity and optimization to guarantee travelers the most suitable mode of getting to their destination whilst being informed of the potential factors that could affect their journey (such as real-time weather and traffic updates).

Once the previous three pillars have been put in place, only then can the mobility operator neatly tie the several components of the MaaS system together.

This is still a critical point as to whether a MaaS system is successful or not because the user experience and friendliness must encourage users to continue using the service rather than going back to their personal vehicles.

Mobility operators such as Trafi and Moovit are prime examples of MaaS application providers that offer their users a seamless experience.

What does the App process look like?

As we continue to transition to a more unified transport system where we are exchanging our car keys for scooters, it seems that MaaS underpins the essence of a shared economic model that ultimately results in a healthier, more sustainable way of moving.

To conclude Sengerio’s third chapter in the mobility management miniseries, we have observed MaaS systems that are still in the early days. Only time will truly reveal how efficient MaaS can be and whether it really can revolutionize our communities.

‘Transition’ implies patience. And we are already seeing the minor changes to urban transport systems that are having a big effect on our climate goals and demand management.

ABOUT SCOTT FRANKLAND

Scott Frankland is Head of Content at Sengerio. His spirit of inquiry leads him to the world of transportation and mobility to connect with the industry’s leading experts and shine a light on the hot topics.